When a patient presents with abnormal bleeding and you are concerned about endometrial hyperplasia, do you immediately biopsy or do you first turn to ultrasound? Does it matter? I think it does.

Personally, I believe doing the endometrial hyperplasia ultrasound first makes the most sense. Ultrasound is readily available in most office and hospital settings. A quick but thorough scan adds invaluable information about the endometrium, uterus and adnexa. Your best shot at measuring the endometrium is before it is disturbed by the biopsy. You may also detect a focal abnormality or the presence of masses, which could lead you to triage the patient to hysteroscopy next rather than biopsy.

Defining Endometrial Hyperplasia

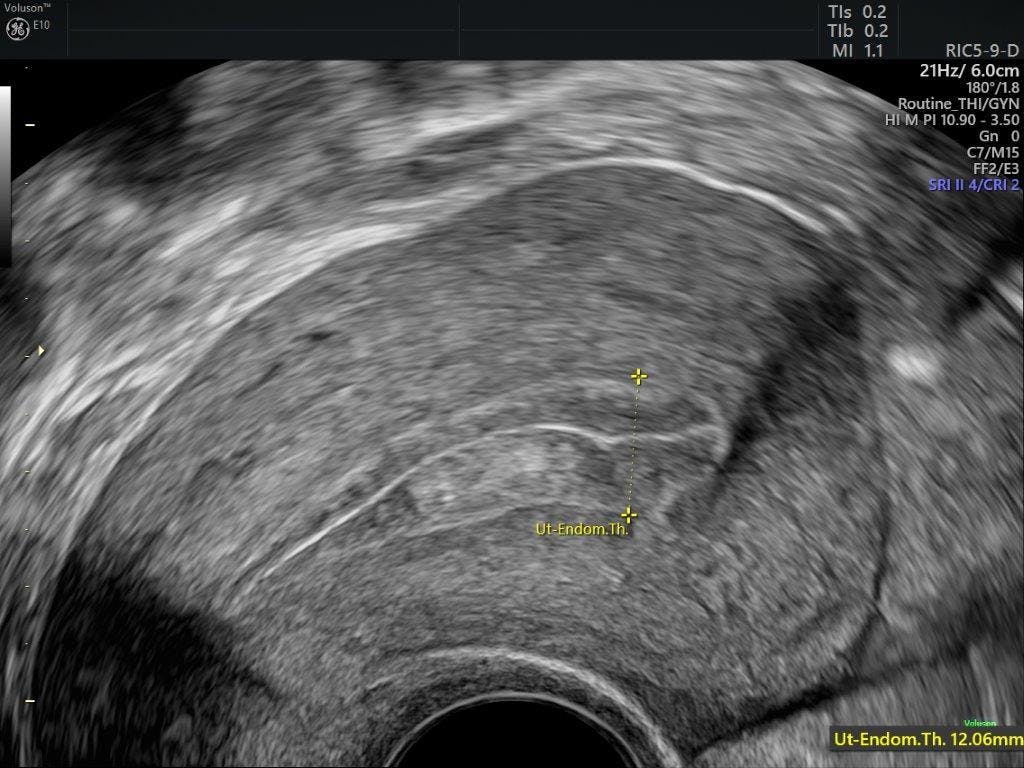

Endometrial hyperplasia is a histologic diagnosis often made after sampling an endometrium that appears thickened on pelvic ultrasound. It is defined as an irregular proliferation of endometrial glands with an increased ratio of gland to stroma. The endometrial thickness should be measured at its thickest point, with calipers placed from one echogenic border to the opposite echogenic border, perpendicular to the endometrial stripe. If any fluid is present in the cavity, it should be subtracted from the measurement.

When reviewing the endometrial appearance on ultrasound, there is some overlap between a normal endometrial thickness and what actually constitutes an abnormal endometrium ultrasound. Knowledge of normal ranges of the endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle and in menopause, combined with a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for endometrial sampling, will help you reach a definitive diagnosis through endometrial hyperplasia ultrasound. Surgical sampling becomes necessary if office sampling does not provide a sufficient specimen for evaluation, or if abnormal bleeding persists despite a previously negative report.

Understanding Why Early Diagnosis Is Critical

The simplified World Health Organization (WHO) definition classifies hyperplasia into two groups, depending on the presence or absence of histologic atypia:

- Hyperplasia without atypia; or

- Atypical hyperplasia/endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN).

The first has a low risk of progressing to become cancer — less than 5 percent over 20 years, according to a Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists study titled "Management of Endometrial Hyperplasia" — and can be treated medically. EIN has a much higher risk of becoming cancer and usually requires definitive surgery.

Endometrial hyperplasia is thought to be caused by unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium without the counteraction of progesterone. Patients at greatest risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia include those with a high body mass index (BMI) due to increased aromatase conversion of ovarian androgens in adipose tissue, anovulation due to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or peri-menopause, or estrogen producing ovarian tumors. Patients who take exogenous drugs such as tamoxifen or hormone therapy are also at risk.

In the U.S., endometrial cancer is the most commonly diagnosed gynecologic cancer and the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and intervention is of utmost importance in reducing the prevalence of endometrial cancer.

Choosing Ultrasound for a Front-Line Approach

Although histologic evaluation is critical, ultrasound imaging has an equally important role in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding, which is the most common presentation in a woman with endometrial hyperplasia.

Maybe it isn't a question about the chicken or the egg. As a classic 1994 report by Dr. Steven Goldstein stated, "Look at the doughnut rather than the hole." In other words, do the ultrasound, then poke a hole in the doughnut.