Embryo freezing has been part of the in vitro fertilization (IVF) process for years. For some IVF patients, cryopreservation of all embryos and deferring transfer to a later cycle can lead to better clinical outcomes. For some women, social egg freezing (oocyte preservation for non-medical reasons) means that they will be using IVF to conceive later, and freezing all eggs that are retrieved.

During the first three decades of IVF, the principal treatment approach involved administration of hormones to promote multiple follicle developments, egg retrieval from those follicles, fertilization of the eggs in vitro, transfer of embryos (usually two or more) to the uterus and cryopreservation of any remaining embryos for future attempts at pregnancy.

Millions of IVF cycles have been and continue to be managed in this way. But, is this treatment optimal for all patients?

Basic Principles of IVF

The basic principles behind this approach have been understood in animal models of IVF for decades. In these models, embryos are usually obtained by flushing the reproductive tract of one female after mating, followed by transfer of the embryos to a second, hormone-primed foster female. If eggs were obtained from one animal and transferred during the same cycle into the same animal after fertilization, results would be dramatically decreased due to embryo/uterus asynchrony.

Preimplantation embryos do not attach to the uterus at all times during the menstrual cycle. Their chance of survival is instead dependent on an optimal hormonal milieu, during a period called the implantation window. Depending on the species, this window may only be a few hours long (as in a mouse) or a few days long (as in a human). Transfer the embryo too early, and it will be rejected by the uterus; transfer it too late, and it may be lost to menstruation.

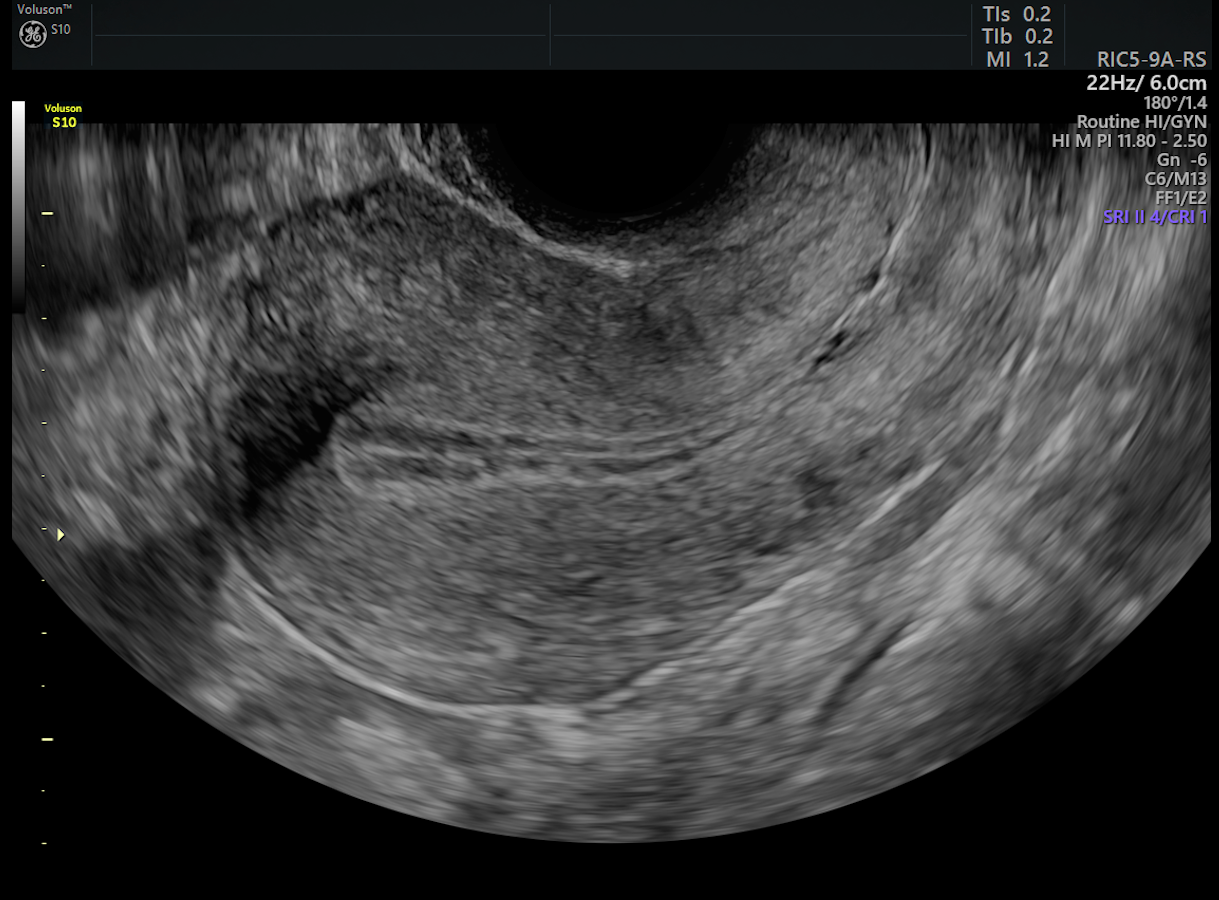

ultrasound image uterus with luteal phase endometrium

Embryo/Uterus Asynchrony and Progesterone Level

Embryo/uterus asynchrony may have dampened results of human IVF all along, which is why deferred transfer may be producing better outcomes. One important factor in the decision to defer transfer and freeze all is progesterone level on the day after triggering ovulation. High progesterone levels suggest that the endometrium may have passed the point of maximum receptivity for embryos. Progesterone serves mainly to regulate the condition of the inner lining of the uterus. Progesterone levels will rise in response to ovarian stimulation, but sometimes the increase may be too quick.

The negative effect of high progesterone on pregnancy outcome stems from its effects on the endometrium and not the embryo itself. By delaying the transfer of embryos until a time when the uterus is not impacted by high progesterone levels, outcomes are improved. Embryo freezing via modern vitrification technologies has facilitated delayed transfer since embryo survival now approaches 100 percent and the concern about the loss of embryos to freezing damage is all but moot.

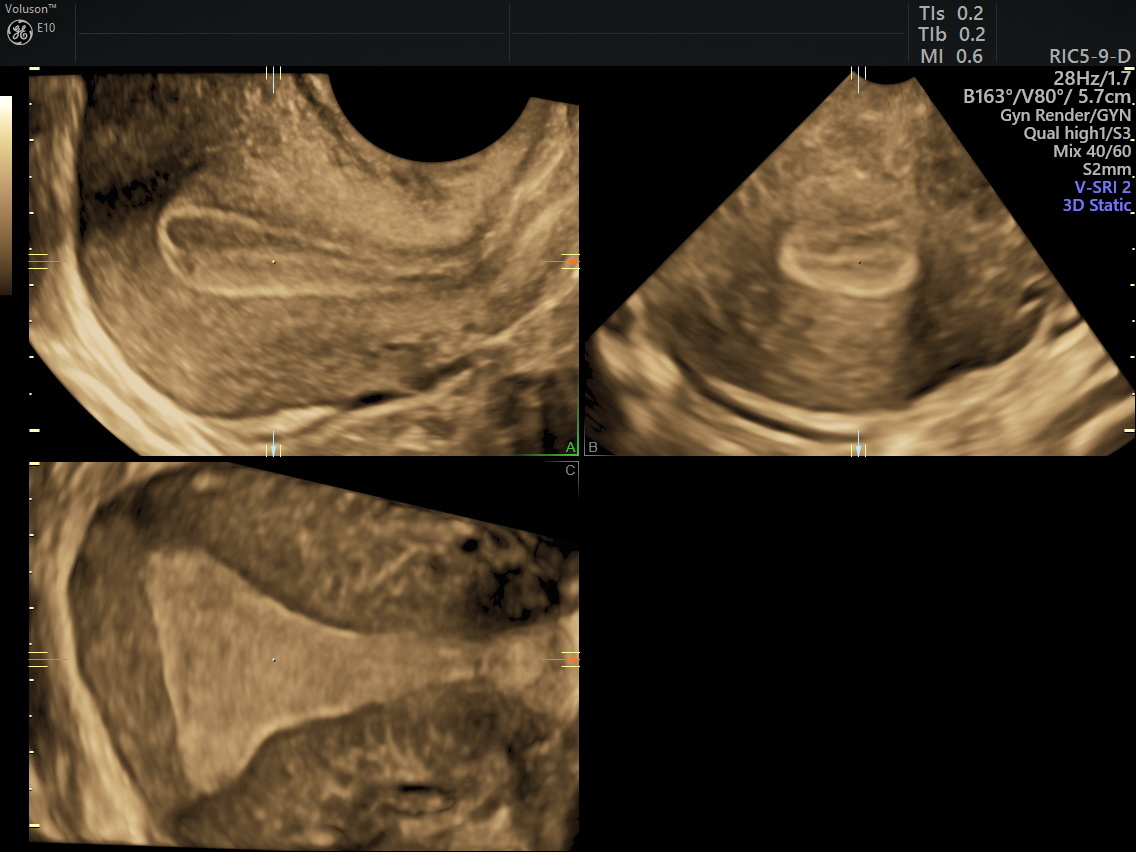

3D ultrasound volume of uterus with normal endometrium

Left top: sagittal uterus: Right top: transverse uterus. These images were used to create the bottom image of a coronal view of the uterus and endometrium.

A Major Change in IVF Protocol

The improved survival rate of frozen embryos and the knowledge about endometrial receptivity, as assessed by ultrasound and the measurement of hormone levels, have together encouraged the recent change in IVF protocols. This shift is based on strong evidence in animal models and was suggested more than 30 years ago. Now patients may choose elective freezing of all their embryos so that they can return later during a natural or monitored cycle and have thawed embryos transferred one at a time until a pregnancy occurs.

The best results with the freeze-all approach are obtained in patients with elevated progesterone at the trigger of ovulation and those with advanced maternal age. Given its overall success, this particular IVF process may be an ideal approach for patients who are looking to conceive.

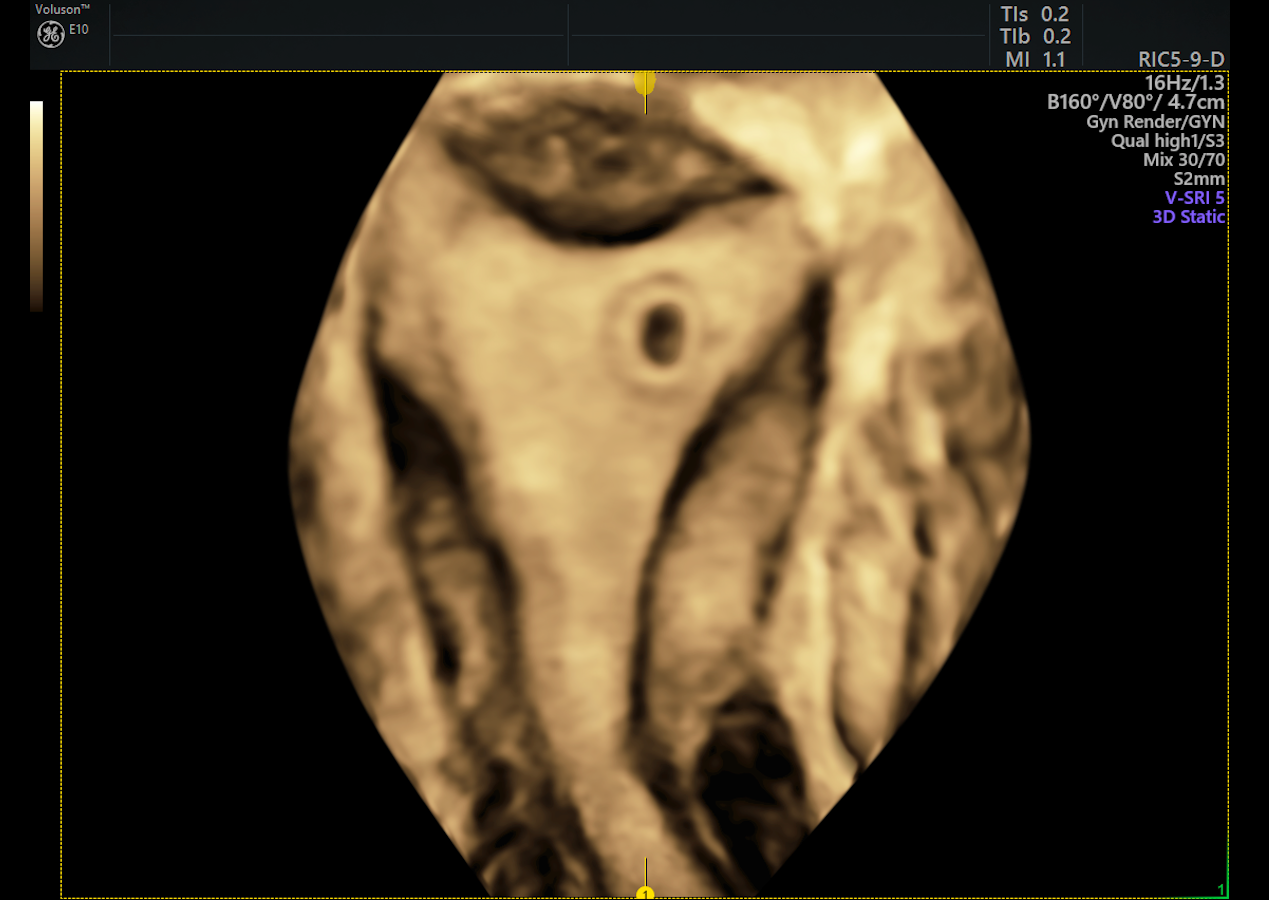

3D ultrasound image of implantation of early pregnancy - at this stage only the gestational sac is seen

Coronal uterus with early gestational sac (darker circle) in left fundal region.