All gynecologists should understand the importance of certain markers at each stage of a patient's life, such as endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women. But what is the best way to measure the endometrium? And when might a patient need this exam in the first place?

Author and practicing gynecologist Dr. Steven Goldstein answered our questions about this assessment, including the best method to use and the role of ultrasound.

Q: Why might a clinician need to measure endometrial thickness in postmenopausal patients?

A: A healthy, postmenopausal woman doesn't generally need this measured. The whole purpose of measuring the thickness of the endometrium is to check the cause of unexplained bleeding: a thin, distinct endometrium in women with bleeding virtually excludes the possibility of cancer. There are some who have mistakenly believed that if an endometrium measures thick in a non-bleeding patient, intervention is needed, but this is not at all the case. There is no evidence to support this. In fact, a lot to refute it.

Q: What is considered a normal endometrial thickness?

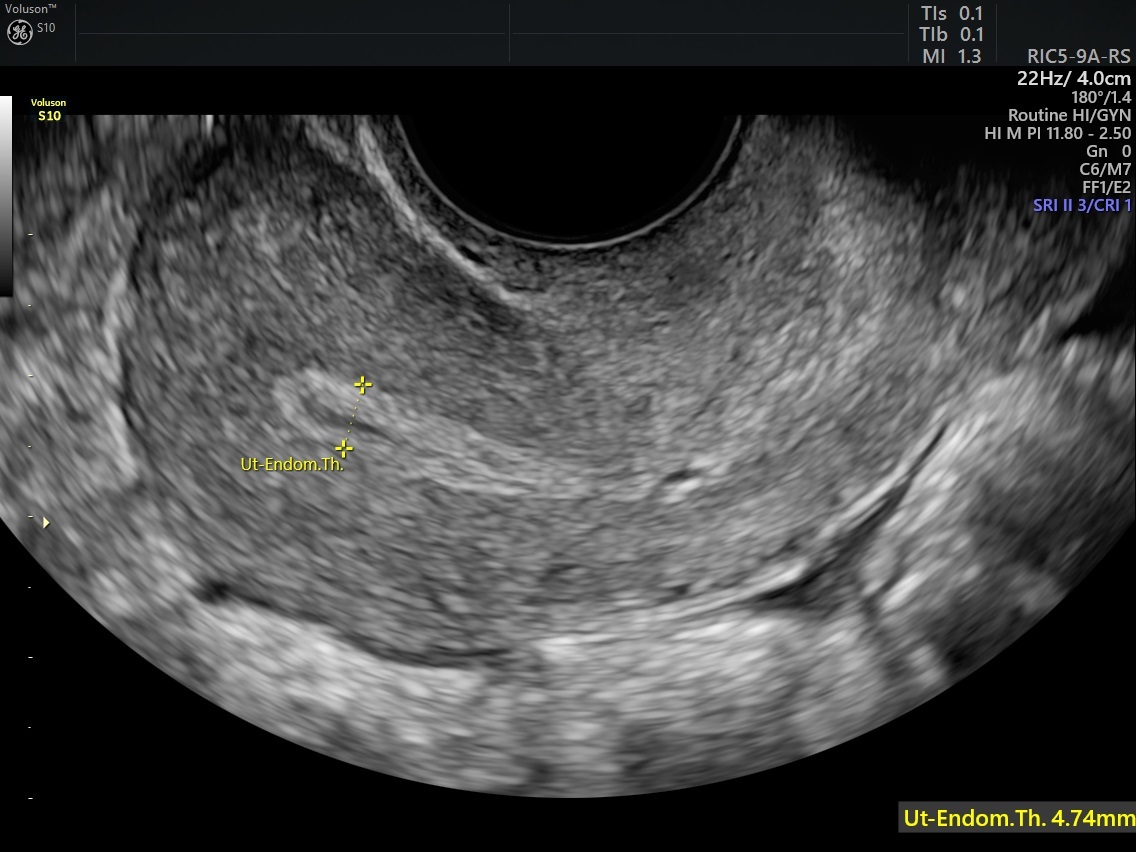

A: There is no true normal in non-bleeding women. In women with post-menopausal bleeding, an endometrial echo of less than or equal to 4 mm is considered normal to effectively rule out cancer. In higher-risk patients with bleeding or patients who "re-bleed," even thinner endometrial echoes may require intervention.

Q: What associated symptoms might a postmenopausal woman with an abnormal endometrium experience?

A: There is good evidence that as many as 17 percent of postmenopausal women will have a so-called thick endometrial echo. The majority of these echoes reveal asymptomatic polyps. One study found that in post-menopausal women with endometrial polyps that haven't bled, the incidence of cancer was 1 in 288.

In the absence of bleeding, endometrial thickness is not automatically a cause for intervention. However, on a case-by-case basis, a clinician may want to further investigate a thick endometrial echo in the presence of risk factors such as obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, hypertension or diabetes.

Q: How does ultrasound play a role in measuring endometrial thickness?

A: The main role of ultrasound is to exclude significant tissue or its high negative predictive value. There is no documented prospective trial showing that a thick endometrial echo needs intervention if the patient is healthy and has no bleeding.

Some studies have implied that the thicker the endometrial echo, the more dangerous, but that's not always true. Most endometrial cancers bleed relatively early. The thickest endometrial echoes, in my experience, tend to be simple hyperplasia or inactive polyps.

Q: What are the key anatomical features a clinician should look for on ultrasound?

A: The key is to measure at a right angle to the endometrial echo on a long-axis view of the uterus (the anteroposterior, or AP, view) at the thickest portion, which is usually about a centimeter from the fundus. Besides thickness, clinicians can look at the irregularity and heterogeneity of the endometrium. If color Doppler is used, sometimes the presence of a central feeder vessel can reveal an endometrial polyp.

Q: What other providers or treatment options might a patient need to seek out after this exam?

A: When it comes to postmenopausal endometrial thickness, in an average-risk woman with postmenopausal bleeding, a thin, distinct echo of less than or equal to 4 mm would require no further intervention.

If an endometrial echo cannot be adequately visualized secondary to coexisting fibroids, adenomyosis, axial uterus, previous surgery or marked obesity, then the next step is often saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) to better delineate the endometrial contents and distinguish global from focal pathology. This is because global pathology may allow for blind endometrial sampling, whereas focal pathology should be dealt with under direct visualization with a hysteroscopic procedure.

Q: What should clinicians keep in mind when assessing and treating older women?

A: Postmenopausal women who have bleeding can be evaluated primarily with transvaginal ultrasound. A thin, distinct echo excludes significant tissue — that means less than or equal to 4 mm in an average-risk woman. If necessary, use SIS to distinguish global from focal pathology and determine the next steps. Finally, a complete ultrasound examination should always include evaluation of the cul-de-sac as well as the adnexal regions, and a search for any adnexal pathology.

Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.