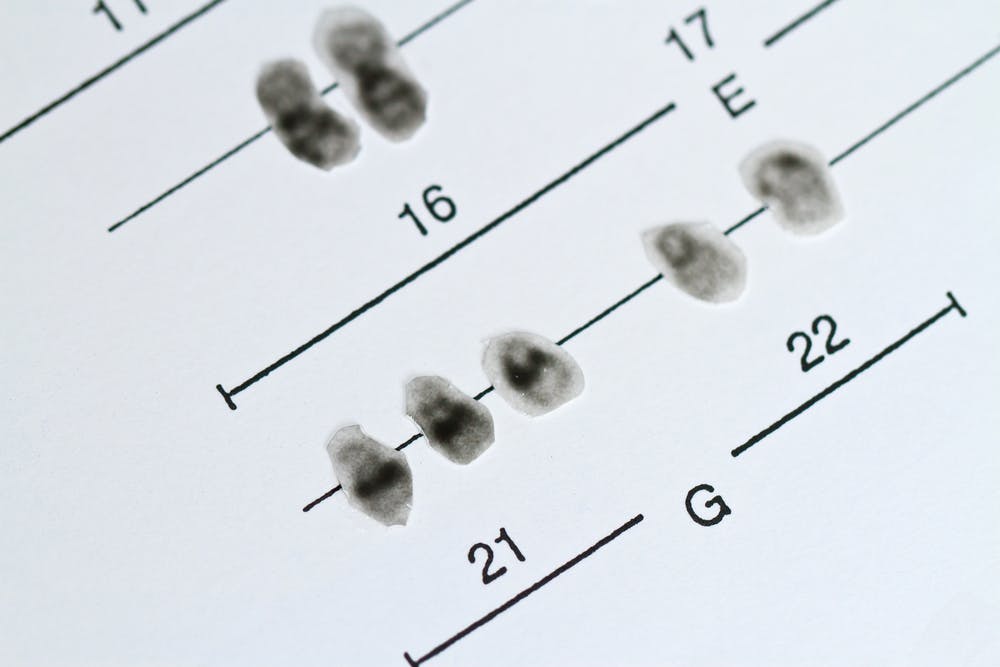

Trisomy 21, a genetic disorder caused by either a complete or partial third copy of chromosome 21, is the most common chromosomal abnormality. The disorder can cause developmental delays, congenital heart defects and facial deformities. Incidence of trisomy 21 increases with maternal age. Carrying out a trisomy 21 screening in the first trimester can help assess whether this disorder is present in the fetus.

Risk Factors for Trisomy 21

Chromosome 21 can experience a full or a partial trisomy, leading to a range of outcomes. The majority of cases of Down syndrome result from a full trisomy of chromosome 21. In the remainder of cases, mosaicism of chromosome 21 or inheritance of a structural rearrangement leads to partial trisomy of the chromosome. Mosaicism and trisomy occur during cell division in the development of the sperm, egg or embryo. In some cases, errors originate during the first meiotic division in the maternal grandmother's body.

The only certain risk factors for trisomy 21 are advanced maternal age at conception and recombination errors. However, other factors have been suggested, such as folate metabolism, as well as environmental, occupational, genetic and epigenetic influences.

Effects of Trisomy 21

Trisomy 21 leads to Down syndrome (DS), which can encompass a variety of birth defects. Roughly half of infants with this chromosomal condition are born with a heart defect. Infants with DS are also at increased risk of developing gastroesophageal reflux, celiac disease, hypothyroidism and problems with hearing and vision. A small percentage of children with the condition develop leukemia.

Intellectual disability and delayed development are also common in children with Down syndrome. Speech and language development typically develop later and more slowly than in children without DS. A small percentage of individuals with DS are also on the autism spectrum.

As they age, people with DS usually experience a decline in cognition starting around age 50. DS is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease: About half of people with DS go on to develop the condition, according to the National Down Syndrome Society.

Prenatal Trisomy 21 Screening

Prenatal screening in the first trimester can help clinicians detect trisomy 21. Cell-free DNA analysis (cfDNA) was introduced in 2011 and has been reported to have a detection rate for trisomy 21 of more than 99 percent, and a false positive rate as low as 0.1 percent, according to research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A comprehensive aneuploidy screening should also consider maternal age, nuchal translucency and maternal serum. Maternal serum is tested for pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and free b-human chorionic gonadotropin (free b-hCG). This form of combined screening detects 90 percent of fetuses with Down syndrome, with a 5 percent false positive rate, according to a multicenter study of 29,137 cases published in the Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Research published in the Singapore Medical Journal proposes that offering high-risk groups, such as pregnant women of advanced maternal age, a cfDNA test in addition to first trimester ultrasound screening may help reduce the number of false positives in women with high-risk screening results. Women with intermediate risk could also be offered cfDNA testing.

Detecting Trisomy 21 With Ultrasound

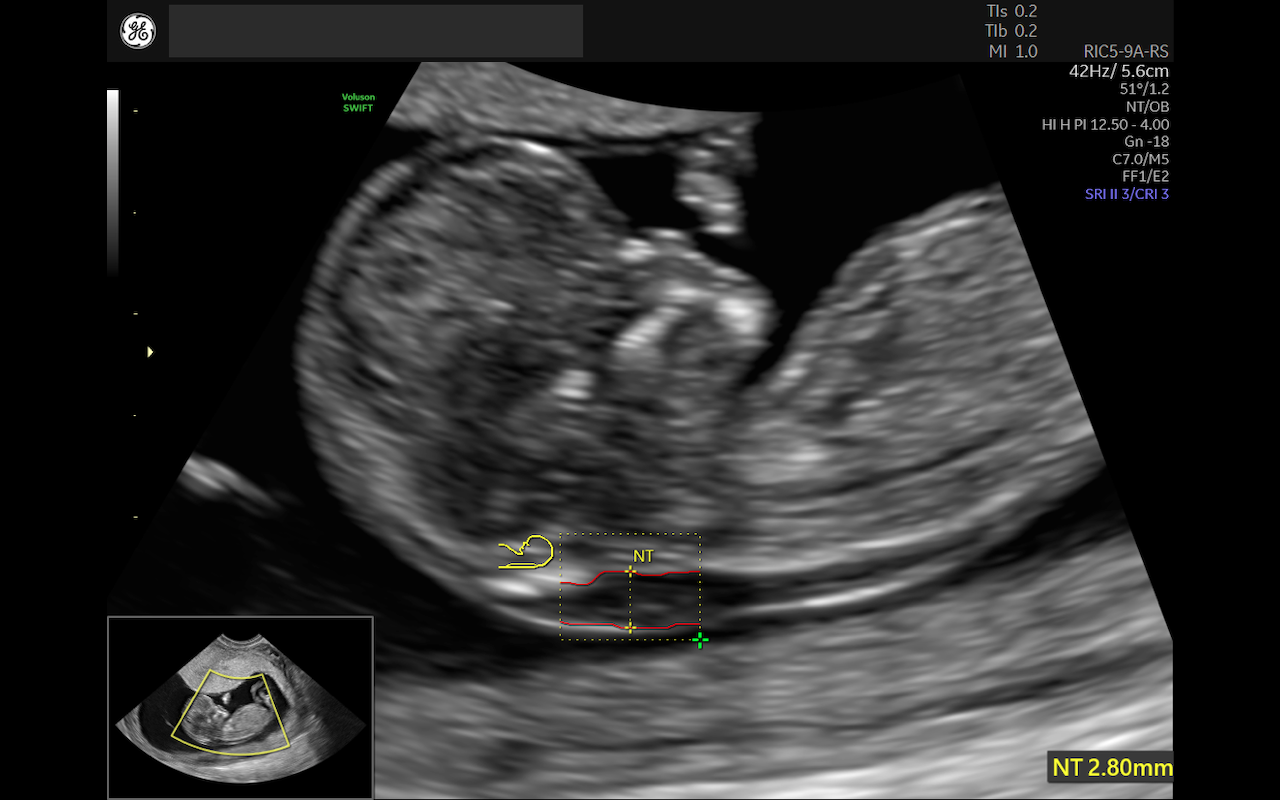

First trimester screening with ultrasound is a more widely used and validated screening modality than cfDNA for the markers of possible trisomy 21. This ultrasound is performed at 11 to 13 gestational weeks and examines the fetal neck for enlarged nuchal translucency (NT). Enlarged NT is associated with chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 21, as well as other aneuploidies like trisomies 18 and 13.

Ultrasound is a critical component of prenatal screening for trisomy 21 and its associated conditions. Trisomy 21 can encompass anomalies in multiple systems, including cardiovascular, craniofacial, central nervous, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and urinary tract. Ultrasound is key for identifying these major structural abnormalities as well as more minor soft markers.

Structural anomalies such as duodenal atresia, septal defects, atrioventricular canal defect, and tetralogy of Fallot are not always detected via ultrasound during prenatal screening. Nuchal translucency, however, can be assessed via ultrasound in the first trimester. NT "reflects the subcutaneous fluid-filled space between the back of the fetal neck and the overlying skin," according to a practice bulletin published by The Society for Academic Specialists in General Obstetrics and Gynecology (SASGOG).

Increased NT measurement is correlated with risk of aneuploidies, including trisomy 21. The detection rate for trisomy 21 is 64 to 70 percent using NT alone, according to the SASGOG bulletin. Other findings include a nuchal cystic hygroma, present in about 50 percent of aneuploidies, and a hypoplastic or absent nasal bone, which was detected in roughly 62 to 70 percent of fetuses with trisomy 21 but was only present in about 1 percent of fetuses without this defect.

Normal Nuchal Translucency measurement

Enlarged Nuchal Translucency measurement

Continued Monitoring in the Second Trimester

If screening results point to a high risk of trisomy 21, it is important to continue monitoring via ultrasound in the second trimester. Soft markers in the second trimester include echogenic intracardiac foci, short femur length, pyelectasis, chord plexus cysts, echogenic bowel, ventriculomegaly and a thickened nuchal skin fold.

If a thickened nuchal fold, ventriculomegaly or echogenic bowel are visible, the predictive value of these findings high enough to prompt further genetic counseling as well as additional screening and testing, according to SASGOG. Soft markers should prompt trisomy 21 and other aneuploidy screening if it has not already been completed.

Multiple soft markers raise the probability of trisomy 21. However, increased nuchal skin fold as an isolated finding "confers the highest risk of aneuploidy and is the most powerful second trimester ultrasound marker, according to SASGOG, which reports a greater than 99 percent specificity for trisomy 21.

Ultrasound alone cannot provide the basis to diagnose or exclude trisomy 21. However, it can increase sensitivity when used in conjunction with cfDNA and first and second trimester screening. When screening test results are positive, diagnostic testing such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling should be offered to patients.