Monitoring the fetal heart during pregnancy offers a window into developing fetuses' health. For obstetric sonographers and physicians who screen for fetal anomalies, this seemingly straightforward process requires practice, skill and considerable anatomical knowledge to produce the high-quality images needed to properly diagnose possible congenital heart defects (CHDs).

Considering the Numbers Behind Congenital Heart Defects

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, congenital heart defects affect around 1 percent of babies born each year in the U.S. The incidence of some types of CHDs is also increasing — about 1 in 4 babies born with a CHD will have a critical CHD.

The most common CHD is the ventricular septal defect, which affects 1 in 240 births. Although this condition is usually diagnosed after birth, its severity can vary widely, and it sometimes resolves on its own. Other noncritical fetal heart defects may require surgical intervention but can be diagnosed during pregnancy via ultrasound, including:

- Atrial septal defect (1/1859 births). This condition is sometimes not diagnosed until adulthood.

- Atrioventricular septal defect (1/1859). This condition is common in babies with Down syndrome.

Critical Congenital Heart Defects

Eight CHDs are considered critical congenital heart defects and almost always require surgical intervention. Fortunately, ultrasound can help detect most of them. They include:

- Coarctation of the aorta (1/1,800 births). This condition is almost always diagnosed after birth

- Tetralogy of Fallot (1/2,518). This condition is associated with Down syndrome

- Transposition of the great arteries (1/3,413)

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (1/3,841)

- Pulmonary atresia (1/7,100)

- Total anamalous pulmonary venous return (1/7,809). This condition is not commonly detected during pregnancy

- Tricuspid atresia (1/9751). This condition is sometimes accompanied by transposition of the great arteries

- Truncus arteriosus (<1/10,000)

Risk Factors for CHD

Specific risk factors for CHD include maternal diabetes, smoking and certain medications, reports research from the Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. However, the cause remains largely unknown.

Chromosomal or genetic changes offer one potential culprit, but there are no tests for genes associated with fetal heart defects. (One exception is first-trimester screening for Down syndrome, which is associated with specific types of CHDs.)

Understanding the Implication of Missed Cases

Because it is possible to diagnose most types of CHDs during pregnancy via ultrasound, it makes sense to assume that most are diagnosed. However, research published in Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology reports that around half of CHDs are missed: Identification rates vary from 30 to 60 percent. This carries weight as a factor in infant morbidity and mortality, since infants with heart problems may require very specialized care very shortly after birth. Having the diagnosis before that point enables the obstetric care team to arrange for delivery in a facility that offers specialized neonatal care.

The Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology review authors cite a separate study published in BJOG that examined second-trimester standard anomaly screening in the Netherlands; the study reviewed 114 records and found that nearly 51 percent of cases with a severe CHD were missed. The missed cases had lower quality scores for the ultrasound exam itself, magnification was not properly used and quality scores were lower in the individual cardiac planes.

In about half of the missed cases, the CHD was not visible on the scan due to poor quality. In nearly a third, the abnormality was visible but went unrecognized. In one-fifth of cases, the CHD was not visible despite having quality images. The results lead the authors to point out the value of adequate training and note that sonographers must also perform a significant number of anomaly screenings to increase their skill in detecting this common birth defect.

A literature review published in Obstetrics & Gynaecology found that first trimester screening at 11-14 weeks' gestation yielded similar results as second trimester screening. In a non-high-risk population of 1,445 major cardiac anomalies that were identified, 767 appeared during first trimester screening. In a high-risk population, 480 major cardiac anomalies were identified, including 338 spotted during first trimester screening. Notably, there were 43 and 20 false-positive cases, respectively.

Screening To Improve CHD Outcomes

Not only does diagnosing a CHD before delivery give the obstetrician information about what services may be relevant both before and after birth, but it also helps the family prepare for the child's needs. Research published in Translational Pediatrics notes that prenatal diagnosis of CHD has the greatest impact in the post-birth period, when intervention may be necessary immediately. However, early diagnosis also allows a fetal cardiologist to better understand the development of the fetus, what type of care team is appropriate for the birth and what needs to anticipate after delivery.

The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology provides (ISUOG) practice guidelines featuring a wealth of information related to performing fetal heart screening exams, such as transducer frequency and level of zoom. The guidelines include ultrasound images alongside anatomical diagrams so that less experienced sonographers can better understand what landmarks to look for.

SonoLyst* – Automatically identifying fetal anatomy seen on standard views to select all applicable annotations to enhance efficiency – compare acquired image/view to standard criteria for quality assurance ensuring image quality and consistency.

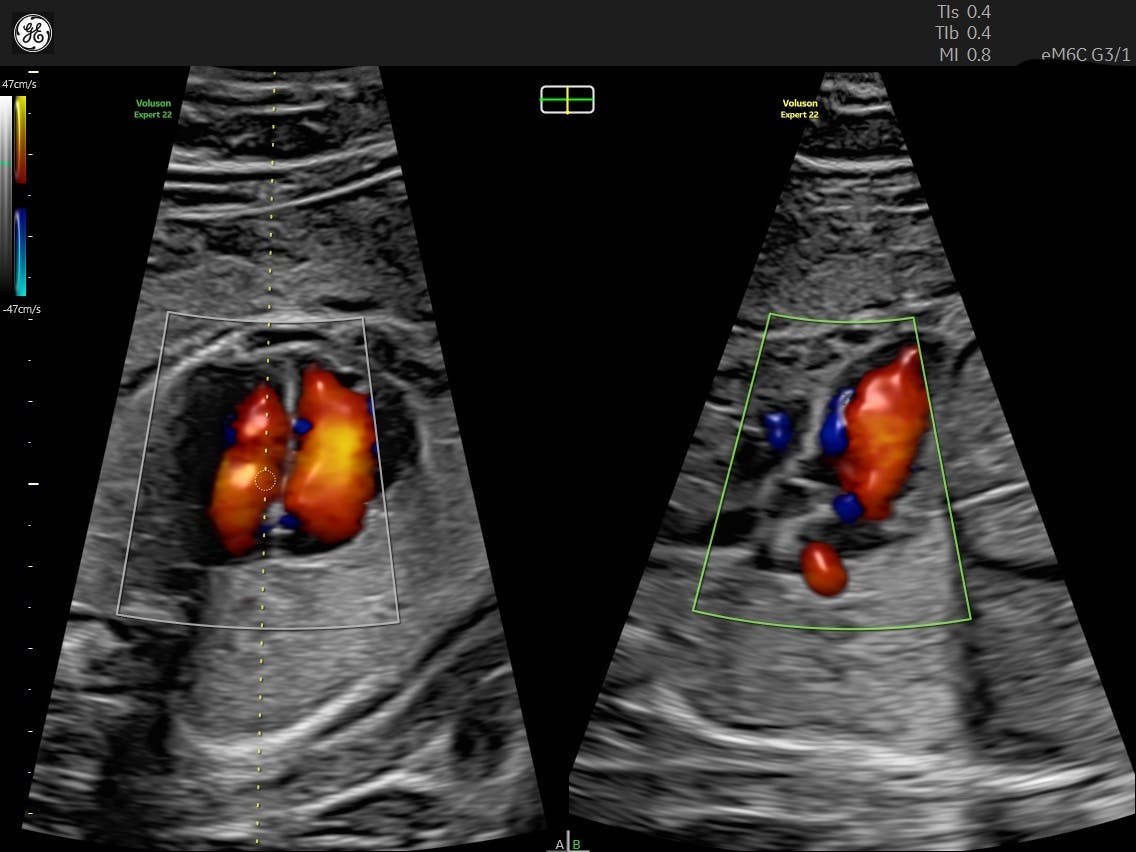

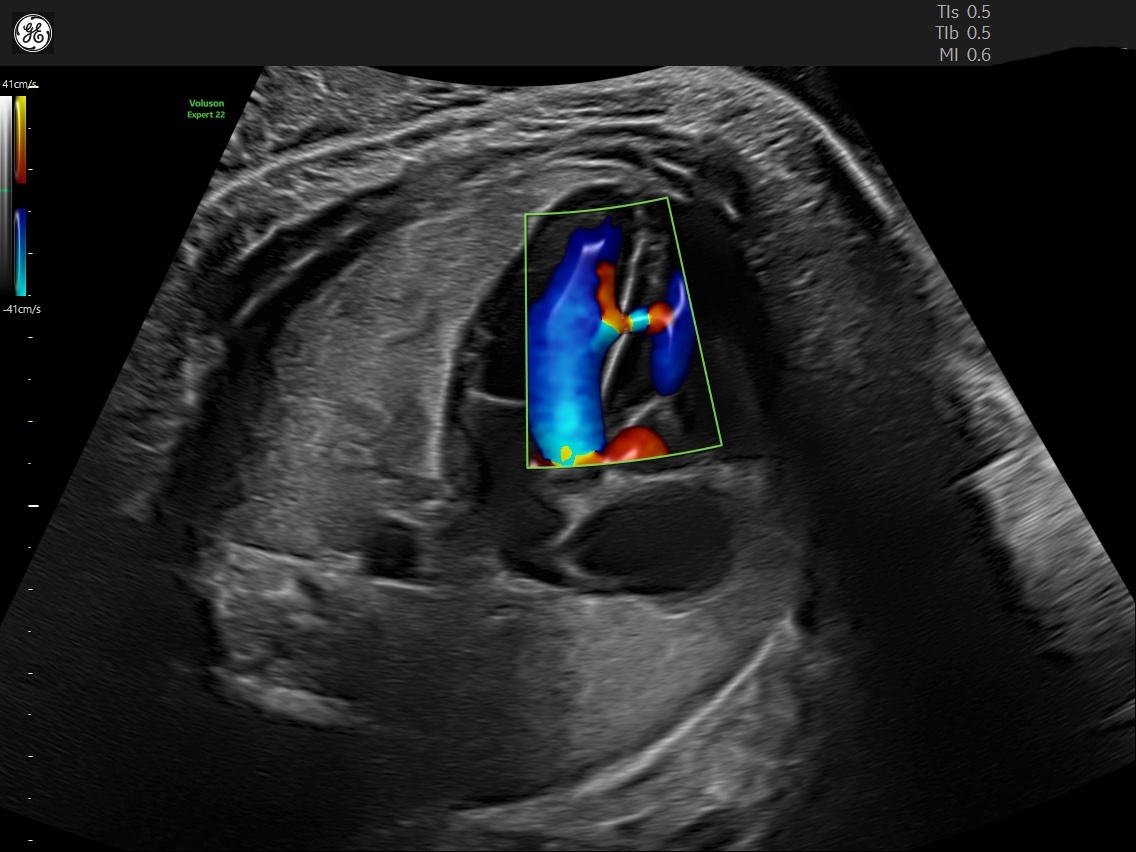

The guidelines have been updated to include the four-chamber and outflow tract views. Color Doppler is "not considered mandatory," but the ISUOG notes that it may improve detection rates in low-risk pregnancies and may be valuable in evaluating patients with larger body habitus. Any scans that result in a suspected CHD warrant a referral for a specialist-performed fetal echocardiogram (ECG). A patient's low-risk status should not deter these referrals, since a large number of cases occur in this population.

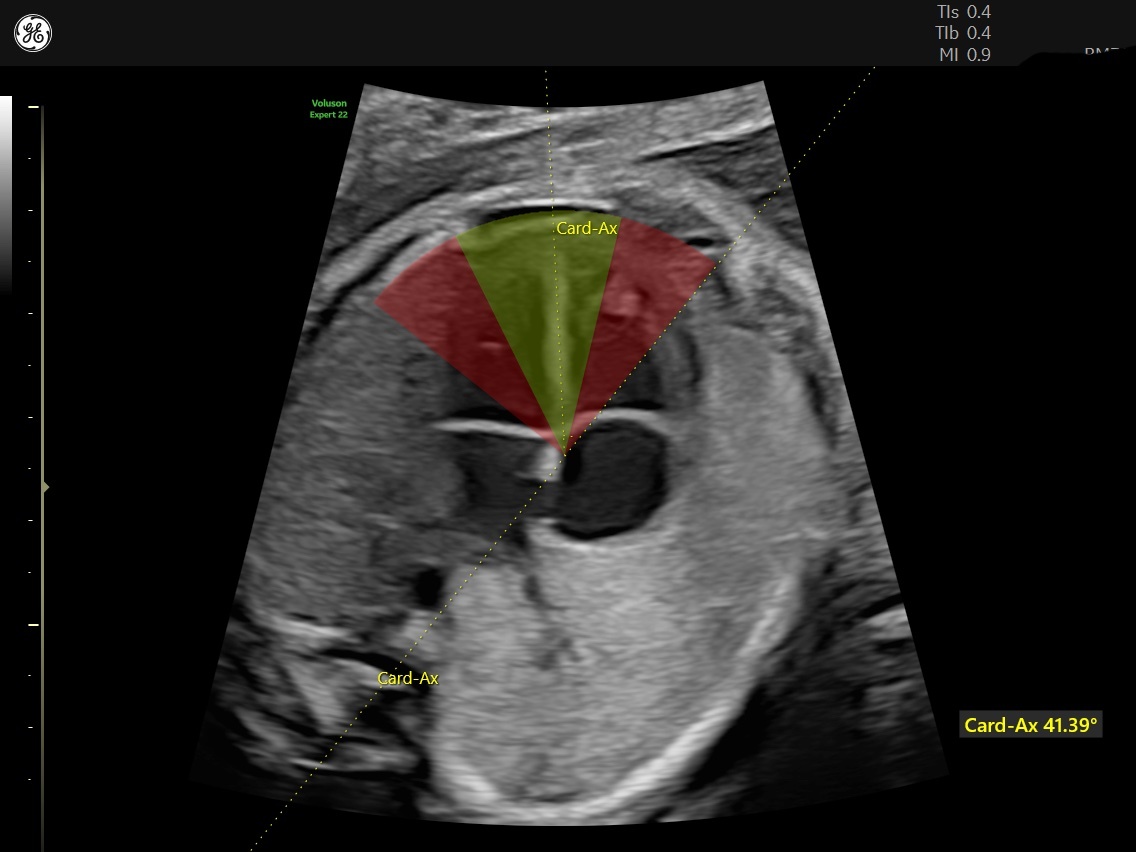

fetalHS helps determine if a fetal heart is normal by guiding you through step-by-step instruction to identify Fetal Situs, 4-Chamber, 3-Vessels and Trachea View, and Cardiac Axis.

Cardiac Axis is an automated measurement to help quickly identify the potential for a congenital heart defect.

Radiantflow™ delivers easy, fast visualization of fetal heart blood flow using the amplitude of the Color Doppler signal to enhance the robustness and create a 3D-like appearance.

The ISUOG also mentions that obstetricians should refer patients for fetal ECG in other cases. The American Society of Echocardiography gives some examples of indications for fetal ECG, including:

- A family history of CHD or certain genetic disorders

- Exposures to teratogens

- Metabolic disorders such as diabetes or phenylketonuria

- Fetal chromosomal abnormality

- Fetal arrhythmia

- Hydrops

- Increased first trimester nuchal translucency

- Multiples such as twins

Although physicians may find value in earlier screening, especially in a higher-risk population, it is common to miss many CHDs during both the first trimester and second trimester exam. Knowing how to properly screen for fetal heart conditions and sufficient scanning experience increases the likelihood of detecting these conditions early, facilitating more careful pregnancy management and planning for postpartum needs.

*SonoLyst incorporates the AI technology of Intelligent Ultrasound.