Copyright© 1988 The American Fertility Society

The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, Mullerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions

The American Fertility Society*

Birmingham, Alabama

The need for standard classification schemes for mechanical problems associated with infertility and fetal wastage is well recognized. In an effort to satisfy this need, The American Fertility Society (AFS) formed a classification committee chaired by Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D. Subcommittees were created to distribute the responsibility for development of the various schemes desired. Committee members were chosen according to their knowledge and desire to contribute. Approval was obtained from the Board of Directors of the AFS and the Executive Committee of The Society of Reproductive Surgeons. Hopefully, editors of medical journals will not accept manuscripts for publication unless they conform to these guidelines. The classification schemes submitted (with a corresponding editorial) are relatively simple to follow. Relevant information can be incorporated into one sheet with appropriate illustrations. In several of the schemes, a scoring system is included to help the surgeon not only document the severity of disease, but to formulate a prognosis. For all schemes a space is provided for the surgeon to note his/her prognosis based upon the extent of pathology and the surgery performed. No classification is perfect, and modification is likely in the future. Use, as well as critique, of these AFS classification is encouraged. All forms, in addition to The Revised-AFS Classification of Endometriosis, will be provided by the AFS administrative office.

Received March 10, 1988. * Drafted by the following committees: Adnexal Adhesions-Editorial: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., Committee: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., James Daniell, M.D., Richard Dickey, M.D., Victor Gomel, M.D., Jerome Hoffman, M.D., Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., Luigi Mastroianni, Jr., M.D. and Thomas Vaughn, M.D. Distal Tubal Occlusion-Editorial: Victor Gomel, M.D., Committee: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., Victor Gomel, M.D. and Carl Levinson, M.D. Tubal Occlusion Secondary to Tubal Ligation-Editorial: Alvin Siegler, M.D., Committee: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., Carl Levinson, M.D. and Alvin Siegler, M.D. Tubal Pregnancies-Editorial: Alan DeCherney, M.D., Committee: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., Alan DeCherney, M.D. and John Rock, M.D. Mullerian Anomalies-Editorial: William Gibbons, M.D., Committee: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., S. Jan Behrman, M.D., Williams Gibbons, M.D., Howard Jones, M.D. and John Rock, M.D. Intrauterine Adhesions-Editorial: Charles March, M.D., Committee: Veasy C. Buttram, Jr., M.D., Alan DeCherney, M.D., Charles March, M.D., Robert Neuwirth, M.D. and Thomas Vaughn, M.D. Reprint requests: The American Fertility Society, 2140 11th Avenue South, Suite 200, Birmingham, Alabama 35205.

Adnexal adhesions

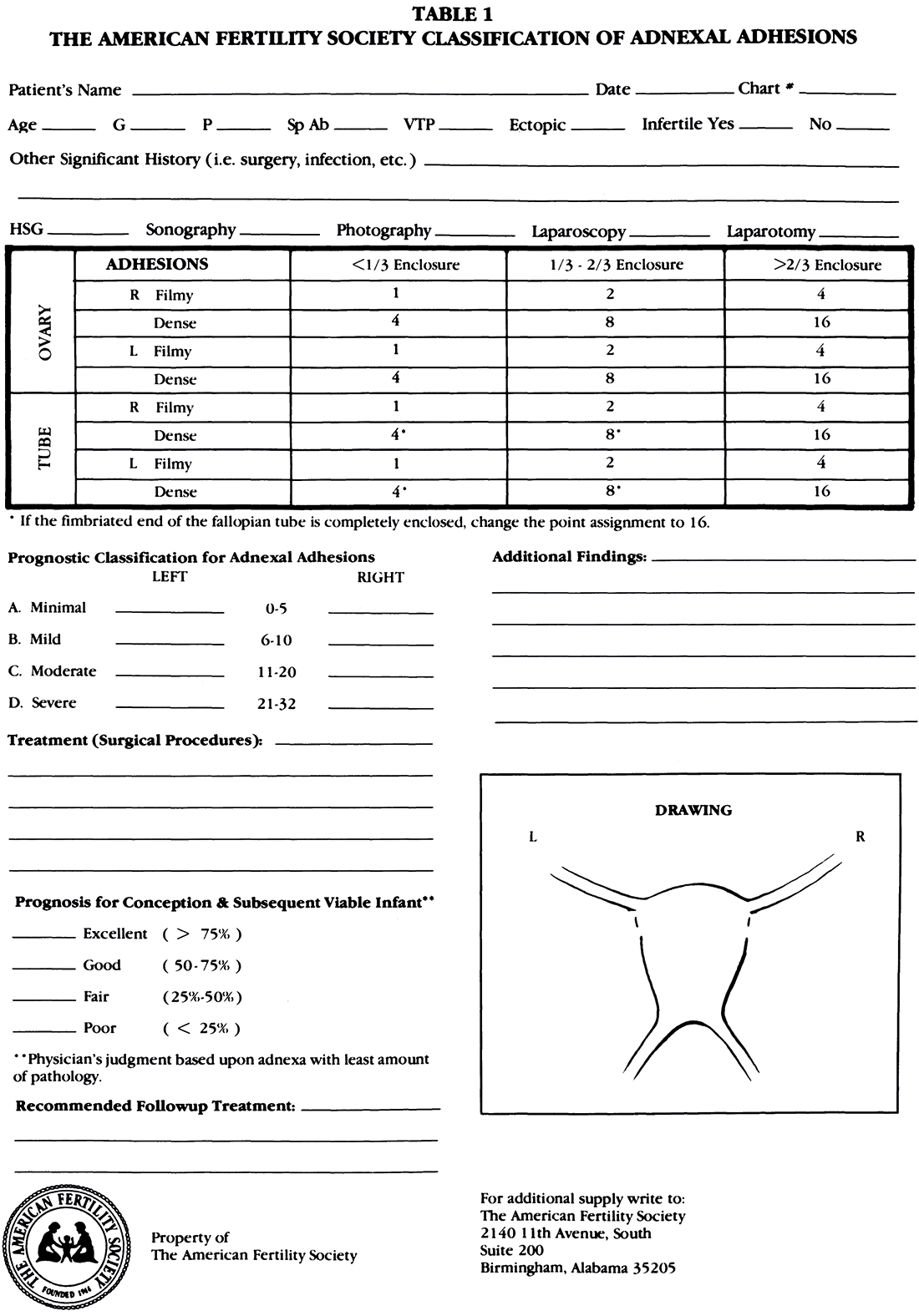

This classification (Table 1) is a modification of the scheme for adnexal adhesions provided in the Revised AFS Classification for Endometriosis.l Although the scores applied to differentiate between minimal, mild, moderate, and severe adhesions are arbitrary, they are considered appropriate until prospective studies are performed that dictate the need for change. Important features of this scheme are that (1) the prognosis for conception is based on the score applied for the adnexa with the least amount of pathology, (2) the importance of the fimbriated end

of the fallopian tube is emphasized, and (3) a differentiation is made between filmy and dense adhesions. The latter subjective observation may create conflict among gynecologists. However, it is the responsibility of the physician to make judgment not only of the extent of the disease, but a distinction between what are thought to be filmy and dense adhesions. Generally, filmy adhesions can be lysed by scissors, electrocautery, or laser without undue risk of bleeding or injury to adjacent organs.

Distal tubal occlusion

Salpingostomy (salpingoneostomy) is the creation

of a tubal ostium in a tube with a totally

occluded fimbriated end as is found in a hydrosalpinx

or sactosalpinx.2

The Ad Hoc Committee of the International

Federation of Fertility and Sterility (IFFS) classified

salpingostomy (salpingoneostomy) as (a) terminal,

(b) ampullary, and (c) isthmic.3,4 A terminal

salpingostomy is preferable since the tube is conserved

in its entirely and normal tubo-ovarian relationships

are maintained. Specific circumstances

such as the presence of extensive intratubal adhesions

in the terminal portion of the tube may oblige

the surgeon to excise the affected portion of the

oviduct and resort to an ampullary salpingostomy.

Reversal of a prior fimbriectomy (Koerner's sterilization)

also requires an ampullary salpingostomy;

this is outside the scope of this editorial, which is

limited to distal occlusion caused by pelvic inflammatory

disease. Isthmic salpingostomies have an

exceedingly poor yield and should be abandoned.

The utilization of microsurgical techniques in

reconstructive infertility surgery has yielded significant

improvements in the results of these procedures.

However, improvements in outcome have

not been as evident in salpingostomy for hydrosalpinx

despite the high postoperative tubal patency

rate obtained with microsurgery. The relative improvement

in the rate of intrauterine pregnancy

noted after such procedures may be due to the increase

in the rate of postoperative patency, which

in turn is also responsible for the significant rise in

the rate of tubal pregnancy. The surgery-pregnancy

time interval after salpingostomy is fairly

long; more than 60% of the patients who achieved

an intrauterine pregnancy did so after the first

postoperative year.5-9

Tubal function, hence the pregnancy rate subsequent

to a salpingostomy for hydrosalpinx, is

largely dependent on the status of the fallopian

tube at the time of the surgical intervention. Individually

and collectively, the following factors affect

the outcome: condition of the endosalpinx, extent

of ampullary dilatation, thickness and rigidity

of the tubal wall, extent and nature of pelvic and

periadnexal adhesions.10 The presence of well-defined

regal markings within the oviduct, especially

when not greatly dilated indicates a good prognosis11

Conversely, intratubal adhesions, especially

when they involve a large part of the oviduct,

represent a contraindication to salpingostomy.12

The prognosis is affected adversely by the extent of

ampullary dilatation, especially if this is more than

3 cmY-15 A hydrosalpinx with rigid, thickened

tubal wall carries an exceedingly poor prognosis.

These tubes show little evidence of dilatation.12,16,17

In addition, the prognosis is inversely proportional

to the extent ofthe periadnexal and pelvic adhesive

process.12-14,16

The tools currently available to investigate the

oviducts are hysterosalpingography and laparoscopy.

They are complementary procedures, and

they are more effective in identifying cases at the

extremes of the spectrum. At one extreme are the

favorable cases, with tubes that show little dilatation,

exhibit rugal markings, are supple without

any suggestion of tubal wall thickening, and without

significant pelvic or periadnexal adhesions. At

the other extreme, the findings are sufficiently severe

to conclude that surgery is contraindicated;

these include the presence of extensive, dense pelvic

adhesions; extensive intratubal adhesions; extreme

dilatation of the tubes; or changes consistent

with or evidence of prior tuberculous salgingitis.

The intermediate cases may be more difficult to

assess. In certain instances periadnexal adhesions

prevent proper visualization and assessment of the

oviduct. Frequently, it is difficult to assess accurately

the thickness and rigidity of the tubal wall

until the time of the actual surgery. The value of

salpingoscopy (performed during the diagnostic

laparoscopy) in predicting postoperative prognosis

is currently under investigation.

The reported viable pregnancy rates subsequent

to microsurgical salpingostomy vary between 19%

and 35%, and the ectopic pregnancy rate ranges

between 5% and 18%. Both intrauterine and ectopic

pregnancy rates increase with longer followup

periods. With favorable cases the outcome is

better; intrauterine pregnancy rates varying between

50% and 80% have been reported.13,16-18 For

this reason, several authors have proposed a scoring

system to identify prognostically favorable

cases. Owing to the progress in the field of in vitro

fertilization, this therapeutic modality has become

a credible alternative to surgery in cases of hydrosalpinx.

This development argues in favor of a

more rigorous selection of patients for microsurgical

treatment. Furthermore, in selected cases laparoscopic

salpingostomy provides another alternative

to microsurgery; this has the advantage of

being performed during the initial diagnostic laparoscopy

without recourse to a laparotomy.19-21 A

better understanding of the prognostic factors will

permit the selection of the most appropriate treatment

modality; this individualization of therapy

should enable us to achieve better overall results.

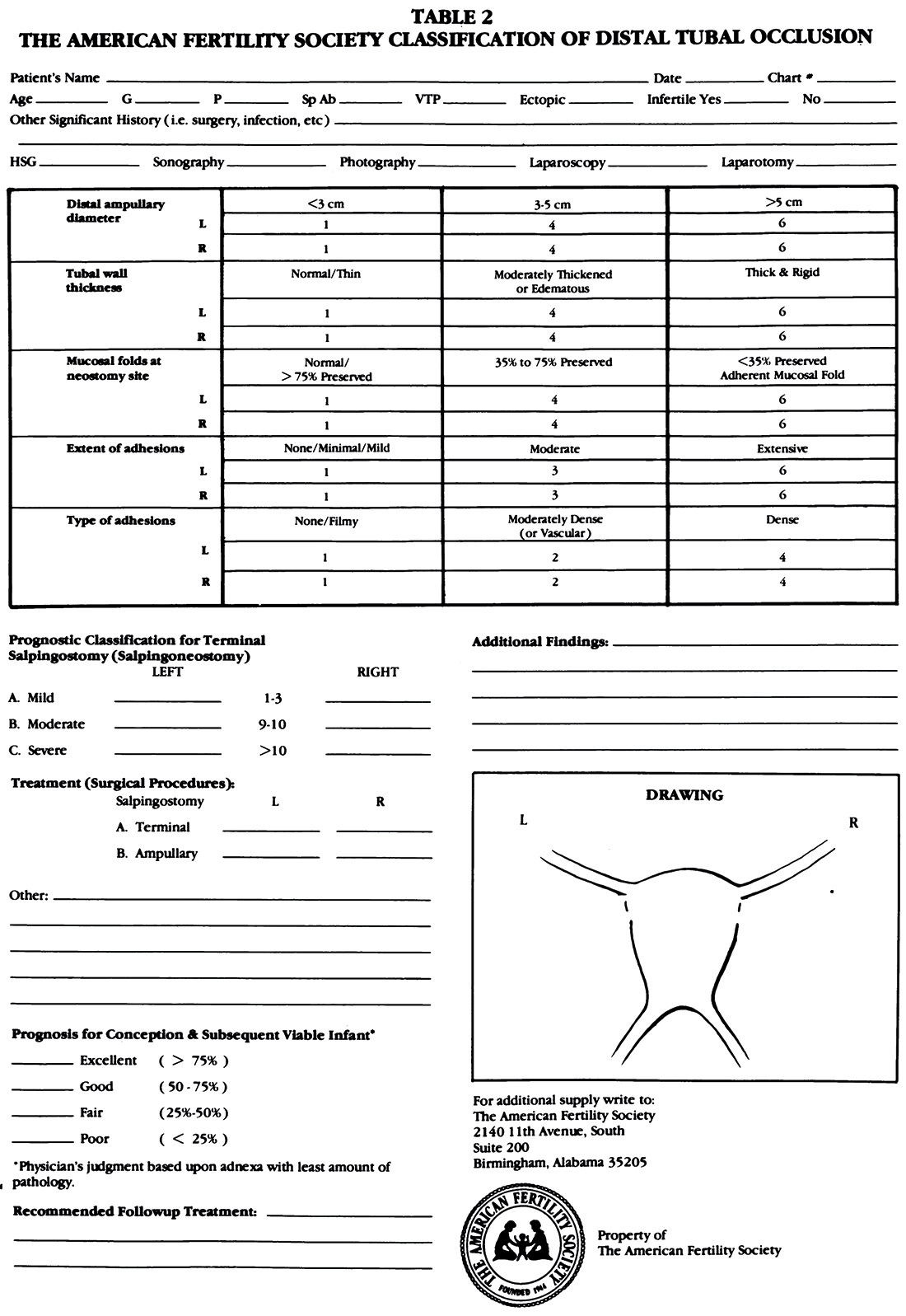

The proposed scoring system (Table 2) has been

devised to predict the postoperative prognosis of

salpingostomies whether performed by laparotomy

or laparoscopy. It has been designed for use at the

time of the actual reconstructive surgery but may

also be employed at the completion of the preoperative

investigation to determine the accuracy of the

information gained. Various factors known to affect

the prognosis have been assigned values. Although

the assignment of specific numbers may

appear arbitrary, they have been selected after

taking into account observations and conclusions

of the previously cited reports. The factors to be

scored include extent and nature (type) of adhesions,

thickness and rigidity of the tubal wall, the

distal ampullary diameter, and the extent of preservation

of mucosal folds in the neostomy site. We

recommend the use of the IFFS classification to

quantify the extent of adhesions, since one already

exists. Minimal/mild: 1 cm of tube and/or ovary

involved. Moderate: adhesions partially surround

tube and/or ovary. Extensive: peritubal and periovarian

adhesions totally encapsulate the tube

and/or ovary. Along with other investigators,22 we

recommend intraoperative salpingoscopy to visualize

the whole length of the ampullary lumen.

Whereas the status of the ampullary endosalpinx is

also an important prognostic parameter, we elected

not to include it in the scoring system at this time,

since salpingoscopy is not being practiced universally.

The proposed classification and the various

values (numbers) in the scoring system will need to

be modified as a result of prospective studies. This

task was undertaken without any illusion that it

would yield the perfect classification; however, a

beginning was necessary.

Tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation

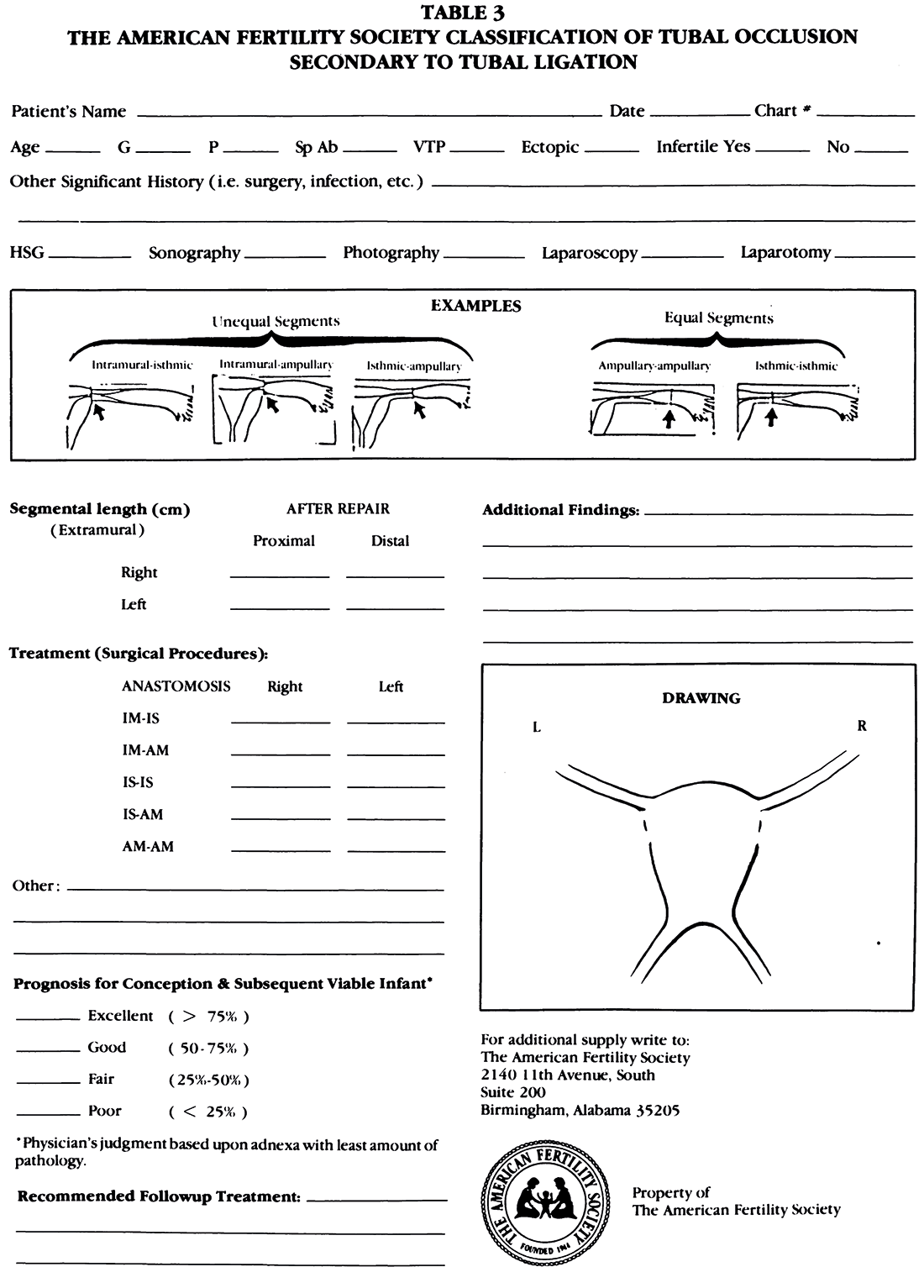

The purpose of this operative classification

(Table 3) is to be able to dentify similar procedures

so that reasonable comparisons can be made

among different studies, prognoses can be given to

patients who then make informed choices, and

physicians can respond to their queries with increased

knowledge.

The type of sterilization can influence the technique

of repair and prognosis. The influence of age

on success is likely. Older women usually have

longer intervals since sterilization, increased ovulatory

disturbances, and older partners. Thus, not

only age but time interval from sterilization to reversal

is important to document. Electron microscopic

studies have shown relative atrophy of the

tubal epithelium in the proximal stumps of women

sterilized more than 5 years prior to reversals and

increased abnormalities between the sterilization

and sterilization reversal (SR). These include flattening

of mucosal folds, deciliation, adenomyosis,

and polyposis. Disorders of the tubal isthmus occur

with chronic (long-standing) occlusion. It is important

to perform a hysterosalpingogram (HSG)

prior to surgery to determine the status of the

proximal portion of the fallopian tubes. Although

laparoscopy is not essential when one is confident

regarding the status of the distal portion of the

fallopian tubes, it is generally advisable.

The lengths of the tubes after completion of the

SR operation should be recorded. The types of

anastomoses are intramural-isthmic, intramuralampullary,

isthmic-isthmic, isthmic-ampullary,

and ampullary-ampullary. Equal-sized lumens

represent either isthmic-isthmic or ampullaryampullary

anastomoses. It is uncommon to encounter

significant periadnexal adhesions in these

women during the SR, and it is not necessary to

add a point scoring system for adhesions. The performance

of other tubal or pelvic procedures and

associated abnormalities should be listed.

Few series of more than 50 SRs have been reported;

postoperatively the live births vary from

48% to 78% and the tubal pregnancies from 1.7% to

6.5%. Since there are an estimated 5,000 reversal

procedures performed annually and less than 1,000

have been reported, it is obvious that most SRs are

being done by the "Silent Majority."

Operations for reversals, other than anastomosis,

include salpingoneostomy and utero-tubal implantation,

the latter involving either the isthmus

or ampulla. The length of the extrauterine portion

of tubal segment should be measured as well as its

new location in the uterine wall. Salpingoneostomy

is done for reversal of a previous fimbriectomy, and

the length of the extrauterine tubal segment should

be noted. Laparoscopy is essential in these patients

before SR is attempted.

A separate classification is needed for anastomosis

operations performed because of pathologic

rather than iatrogenic occlusions. These procedures

have a different prognosis from those done

for SR. Invariably, these women will need a

screening HSG and laparoscopy; however, the categories

for anastomosis are quite similar to those for

SR. We would suggest including a category entitled

"Surgical Pathology Report." The listings would be

luminal fibrosis, salpingitis isthmica nodosa, endometriosis,

tuberculosis, and other. Of concern is

that in approximately 10% of specimens for histologic

examination, no pathologic lesions are found.

Tubal pregnancies

Approximately 60,000 ectopic pregnancies occur

in this country in a single chronologic year, making

surgery for an ectopic pregnancy a frequently performed

procedure in reproductive surgery.

New technology has changed ectopic pregnancy

as an entity, both in diagnosis and in management.

The combination of serial beta pregnancy testing

and ultrasound, both abdominal and vaginal, has

increased our diagnostic acuity so that ectopic

pregnancies are now diagnosed between 6 and 8

weeks gestation, instead of being diagnosed at 10

weeks or later as in the past. This change has

ushered in the age of conservative surgery in the

management of ectopic pregnancy, in contradistinction

to the ablative surgery that was done a

decade ago. At that time, ectopic pregnancies were

diagnosed after rupture has occurred, and very little

in the way of alternative remained.

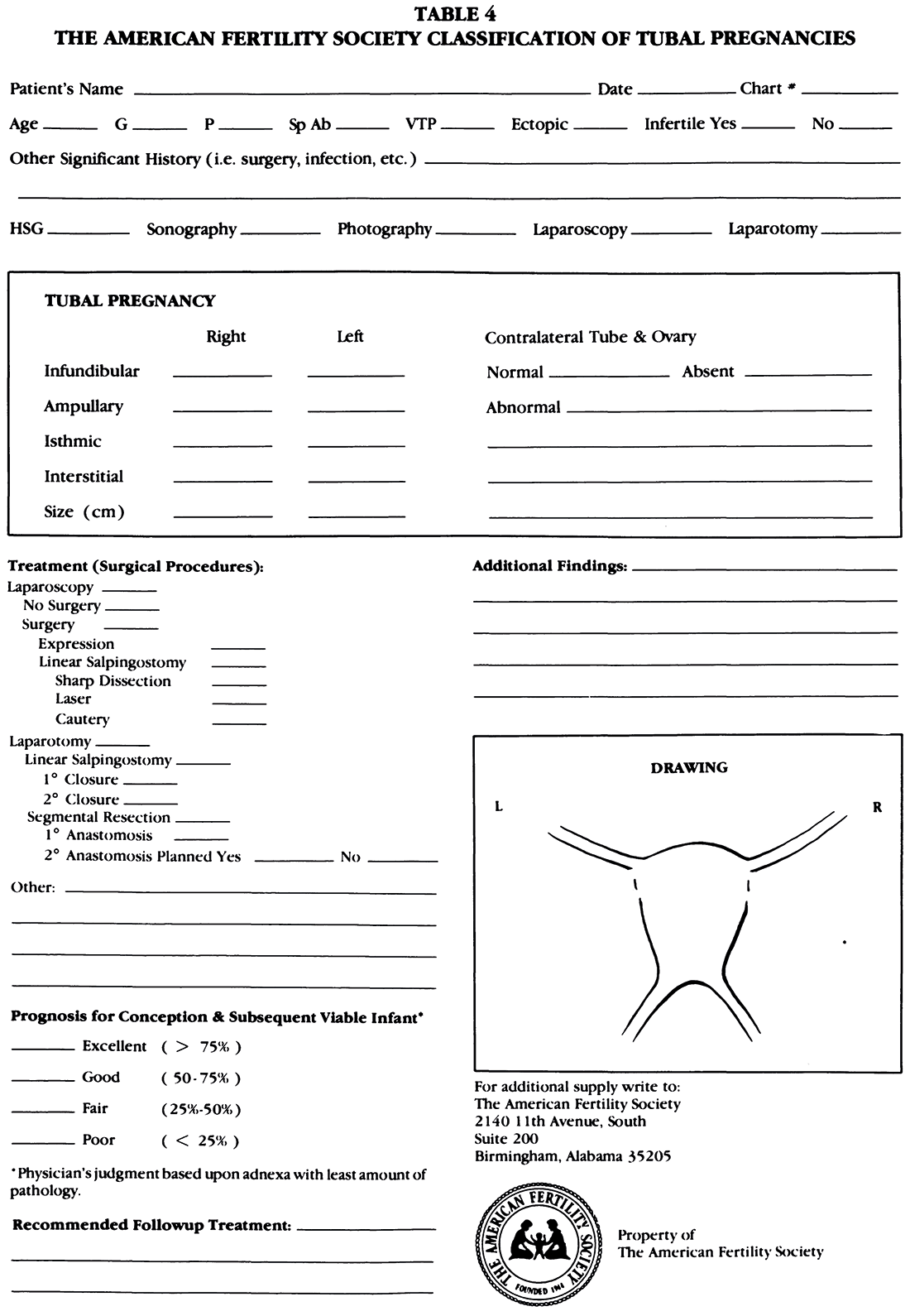

Classification for ectopic pregnancy should be

comprehensive, and not overwhelming. It should be

helpful and informative. Completion of the forms

should be a welcome addition to management,

rather than a chore. This classification of ectopic

pregnancy (Table 4) includes some historic facts

indigenous to the patient that indicate a high risk

for ectopic pregnancy, i.e., previous tubal surgery,

previous ectopic pregnancy.

The anatomic location of the ectopic pregnancy

is critical. Ampullary ectopic pregnancies usually

grow outside of the lumen, and therefore postoperative

patency is to be expected. Linear salpingostomy

seems to be the treatment of choice in these

cases. Conversely, isthmic ectopic pregnancies

grow within the lumen and destroy the tubal mucosa;

in these cases, segmental resection seems to

be the treatment of choice.23 Interstitial pregnancies

in time will most likely be treated by chemotherapy,

not surgery; therefore, this is also important

to note. Ruptured or unruptured should be

noted, and site of rupture, or imminent rupture are

also critical issues since ectopics that rupture into

the broad ligament, rather than dorsally, represent

an entirely distinct entity requiring more extensive

surgery.

It is essential to record the mode of treatment.

Many ectopic pregnancies are now removed by a

laparoscopic approach as opposed to laparoscopic

diagnosis with treatment at laparotomy. The

method of surgical repair should also be included:

magnification vs. no magnification. The method

of surgical approach needs to be elucidated (no

surgery, expression [milking the tube], linear

salpingostomy, or segmental resection with primary

or secondary anastomosis or no anastomosis

planned). Also to be considered in the classification

are other anatomic observations including adhesions,

status of the contralateral tube, and corpus

luteum. And last, adjunctive therapy and postoperative

course are helpful.

In any classification, foresight is the key. What

will you want to know in the future about this particular

patient? This information is critical in

counseling patients about future success rates,

especially now that patients are having multiple

ectopic pregnancies, rather than only two as in the

past.24

Mullerian anomalies

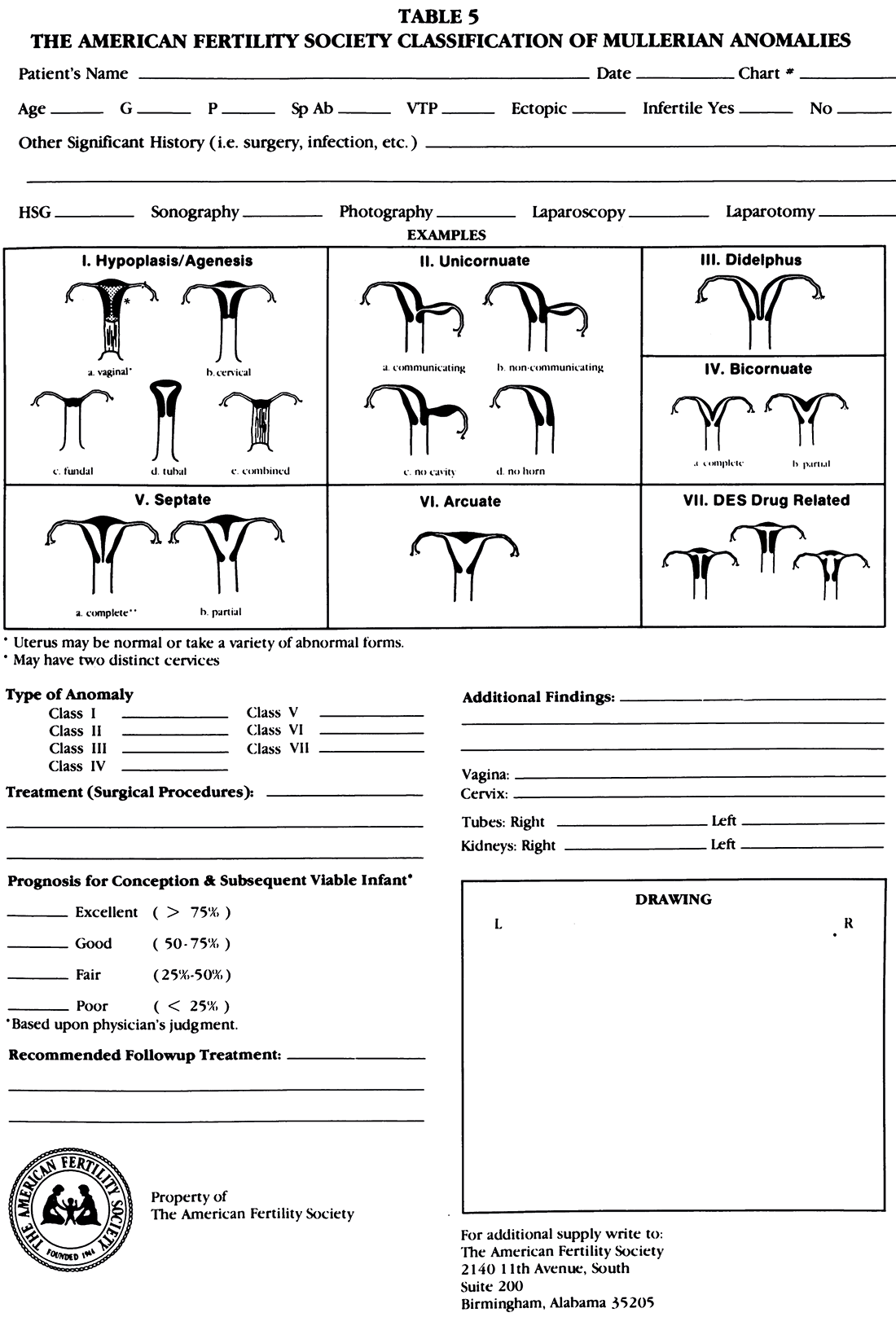

The reason for providing a standardized classification is its value to the practicing physician. It should be simple to use to promote compliance and flexible enough to provide the capacity to fit almost "every" possibility. A frequently used classification by Strassman25 grouped the anomalies into the symmetric double malformations (didelphus, bicornuate, septate) or the asymmetric ones (unicornuate with or without a rudimentary horn). This resulted in a reduction in the amount of available information that reached the literature because of arbitrary groupings particularly with regard to the bicornuate and septate uteri. Consequently, if the clinician wishes to inform, for example, a patient with a unicornuate uterus with a

rudimentary functional horn of her prognosis, the sources are limited to individual case reports or a single series containing few cases. Few reports in the literature provide fetal wastage rates for separate uterine malformations.26-29 The conclusions reached in these individual series vary greatly because they are based on such a small number of observations. An easy-to-use flexible reporting system will allow the clinician to group cases with others so that in the future appropriate conclusions can be reached based on adequate numbers. This classification (Table 5) organizes the anomalies according to the major uterine anatomic types. It allows the user to indicate the malformation type as well as the associated variations involving the vagina, cervix, tubes, ovaries, and urologic system. Later, when data is compiled, a unique "computerizable" code can be generated for reporting purposes. The classification committee had difficulty deciding how to include the arcuate uterus. Because the arcuate uterus is externally unified, it could be classified as a form of a partial septate uterus. However, since in contrast to the other malformations, the arcuate uterus appears to behave benignly, it was thought that it should be classified separately for the present. Thus, data can be generated that can be used to determine if it should remain in a classification of abnormal uterine malformations or is a variant of normal anatomy.

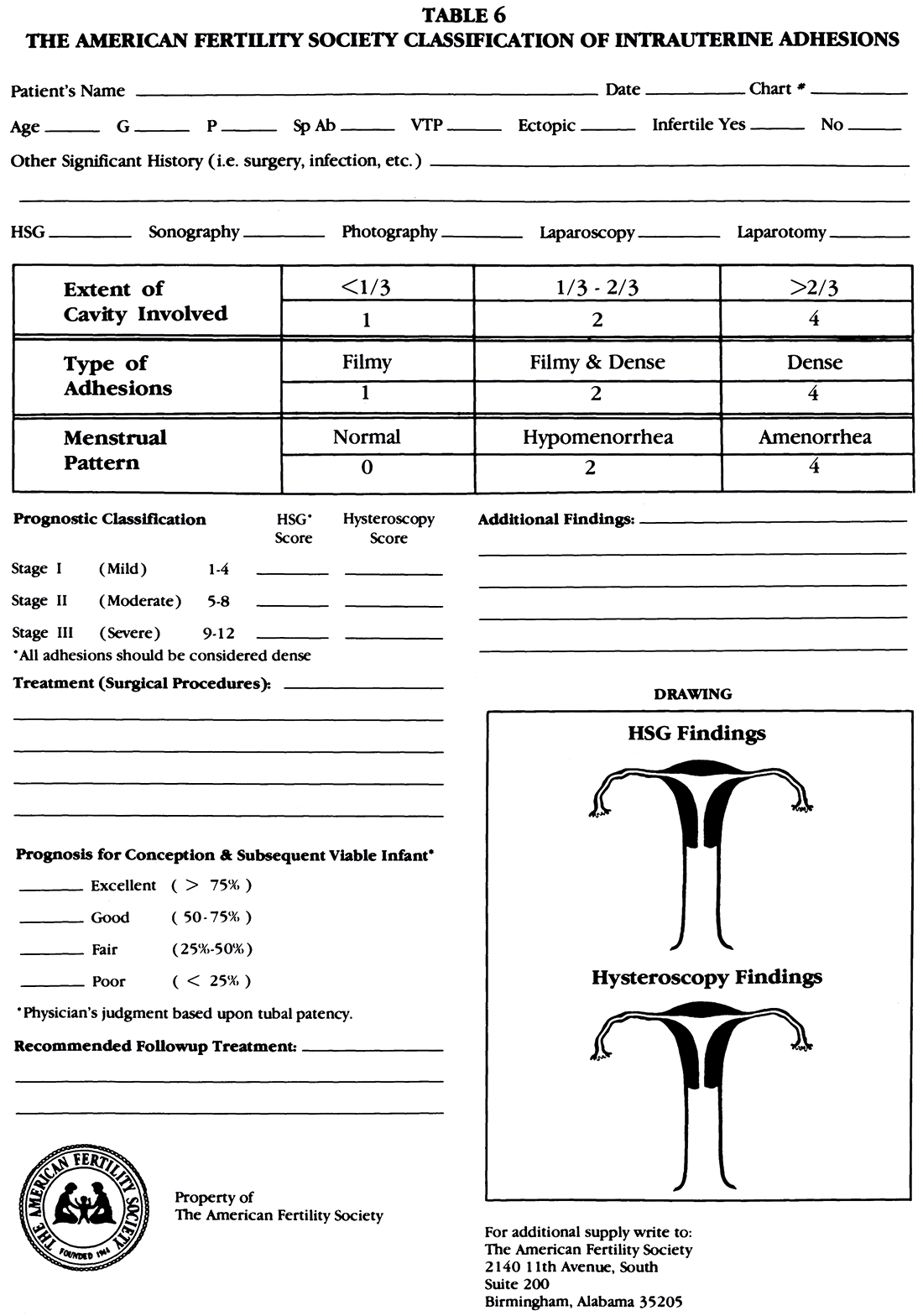

Intrauterine adhesions

The charge to our committee was to develop a

simple classification system for intrauterine adhesions

(IVA). Although other schema to grade IVA

have been available, the widespread use of hysteroscopy

demonstrated their flaws. The first endoscopic

classification was accurate but failed to consider

menstrual pattern, thus the prognostic significance

of endometrial sclerosis or atropy could not

be considered.30

The classification proposed (Table 6) provides

an objective scoring system that permits both the

indirect (hysterographic) and direct (hysteroscopic)

grading of IVA. The location of adhesions is

likely to be of prognostic importance for infertile

women because most implantations occur in the

top-fundal portion of the uterus and because adhesions

in the cornual recesses may cause tubal obstruction.

Drawings should be made to document

location and extent of adhesions. Thus, these findings,

as well as those of laparoscopy should be recorded in the

section entitled "Additional Findings."

The number of classifications of IVA is exceeded

only by the number of treatment regimens. Because

suitable intrauterine contraceptive devices

are no longer readily available to use as "splints"

within the uterine cavity, many treatment schemes

are likely to change. Therefore, these data are even

more important.

Finally, it is advised that one classification form

be completed immediately after surgery and another

following all therapy including the follow-up

hysterosalpingogram or hysteroscopy that is performed

before permitting the patient to attempt

pregnancy. The comparison of the two forms will

provide objective data about the success of therapy

and will permit the true worth of the classification

system to be assessed.

As with the classification system for endometriosis,

continuous evolution is expected. The comparison

with an earlier successful classification reported

in this journal attests to the workability of

the new system. However, broader application may

cause flaws to become more evident resulting in

additions, deletions and/or modifications.

References

1. The American Fertility Society: Revised classification of

endometriosis. Fertil Steril 43:351, 1985

2. Gomel V: Correction of terminal occlusion ofthe oviduct. In

Microsurgery in Female Infertility, Boston, Little, Brown

and Company, 1983, p 163

3. Gomel V: Recent advances in surgical correction of tubal

diseases producing infertility. Curr Probl Obstet Gynecol

1:10, 1978

4. Gomel V: Classification of operations for tubal and peritoneal

factors causing infertility. Clin Obstet GynecoI23:1259,

1980

5. Gomel V: Salpingstomy by microsurgery. Fertil Steril

29:380, 1978

6. Gomel V, Swolin K: Salpingostomy: microsurgical technique

and results. Clin Obstet Gynecol 23:1243, 1980

7. Jansen RPS: Surgery-pregnancy time intervals after salpingolysis,

unilateral salpingostomy, and bilateral salpingostomy.

Fertil Steril 34:222, 1980

8. Russell JB, DeCherney AH, Laufer N, Polan ML, Naftolin

F: Neosalpingostomy: comparison of 24- and 72-month follow-

up time shows increased pregnancy rate. Fertil Steril

45:296, 1986

9. Kitchin JD III, Nunley WC Jr, Bateman BG: Surgical management

of distal tubal occlusion. Am J Obstet Gynecol

155:524, 1986

10. Gomel V: Results of reconstructive infertility surgery. In

Microsurgery in Female Infertility, Boston, Little, Brown

and Company, 1983, p 225

11. Ozaras H: The value of plastic operations on the fallopian

tubes in the treatment of female infertility: a clinical and

radiologic study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 47:489,1968

12. Gomel V: Contraindications. In Microsurgery in Female Infertility,

Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1983, p 129

13. Rock JA, Katayama P, Martin EJ, Woodruff JD, Jones HW

Jr: Factors influencing the success of salpingostomy techniques

for distal fimbrial obstruction. Obstet Gynecol

52:591, 1978

14. Verhoeven HC, Berry H, Frantzen C, Schlosser HW: Surgical

treatment for distal tubal occlusion: a review of 167

cases. J Reprod Med 28:293, 1983

15. Donnez J, Casanas-Roux F: Prognostic factors of fimbrial

microsurgery. Fertil Steril 46:200, 1986

16. Boer-Meisel ME, te Velde ER, Habbema JDF, Kardaun

JWPF: Predicting the pregnancy outcome in patients

treated for hydrosalpinx: a prospective study. Fertil Steril

45:23,1986

17. Mage G, Pouly JL, de Joliniere JB, Chabrand S, Riouallon

A, Bruhat M-A: A preoperative classification to predict the

intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy rates after distal tubal

microsurgery. Fertil Steril46:807, 1986

18. Frantzen G, Schlosser HW: Microsurgery and postinfectious

tubal infertility. Fertil Steril 38:397, 1982

19. Gomel V: Salpingostomy by laparoscopy. J Reprod Med

18:265, 1977

20. Gomel V, Taylor PJ, Yuzpe AA, Rioux JE: Laparoscopy and

Hysteroscopy in Gynecologic Practice. Chicago, Year Book

Medical Publishers, Inc, 1986, p 148

21. Daniell JF, Herbert CM: Laparoscopic salpingostomy utilizing

the CO2 laser. Fertil Steril 41:558, 1984

22. Henry-Suchet J, Loffredo V, Tesquier L, Pez JP: Endoscopy

of the tube (tuboscopy): its prognostic value for tuboplasties.

Acta Eur Fertil16:139, 1985

23. DeCherney AH, Maheuz R: Modern management of ectopic

pregnancy. Curr Prob Obstet Gynecol, Chicago, Year Book

Medical Publishers, 6:9, 1983

24. Silidker J, Tarlatzis BC, DeCherney AH: Fecundite apres

deux grossesses ectopique. Contraception-Fertilite-Sexualite

12:701, 1984

25. Strassman P: Die operative vereinigung eines doppelten

uterus. Zentralbl Gynakol 31:1322, 1907

26. Caprara BJ, Chuang JT, Randall CL: Improved fetal salvage

after metroplasty. Obstet Gyneco131:97, 1968

27. Michalas S, Prebedourakis C, Lolis D, Antasalkis A: Effect

of congenital uterine abnormalities on pregnancy. Int Surg

61:557, 1976

28. Behrman SJ, Musich JR: Obstetrical outcome before and

after metroplasty in women with uterine anomalies. Obstet

Gynecol 52:63, 1978

29. Buttram VC Jr, Gibbons WE: Mullerian anomalies: a proposed

classification (an analysis of 144 cases). Fertil Steril

32:40,1979

30. March CM, Israel R, March AD: Hysteroscopic management

of intrauterine adhesions. Am J Obstet Gynecol

130:653, 1978